Threads of a Nation: Georgian Traditional Fashion

In the heart of the Caucasus, Georgia stands as a crossroad of bold landscapes, deep-rooted history, and living traditions. Here, fashion is more than clothing: it’s a language. Every stitch, fabric, and silhouette tells stories of geography, rituals, and identity. These garments, steeped in symbolism, serve practical purposes while embodying social rank and ceremonial meaning.

The Chokha: Symbol of National Identity

Among Georgia’s traditional garments, the chokha is perhaps the most iconic. A long, tailored tunic once worn by Caucasian warriors, the chokha has re-emerged as a national emblem, now worn during formal ceremonies and patriotic celebrations. Its most distinctive feature is the row of cartridge holders across the chest; once functional, now symbolic.

But not all chokhas are alike. In the eastern regions of Kartli and Kakheti, chokhas are typically knee-length with side slits, tailored from sturdy fabrics in deep, refined colors like black, navy, or burgundy—designed to convey authority and poise. In the mountainous region of Khevsureti, chokhas are shorter and richly decorated, with hand-stitched crosses, contrasting seams, and rough wool - a nod to medieval traditions that still endure.

In the humid regions of Adjara and Guria, chokhas become lighter and more practical. They’re shorter, worn with wide trousers, brightly colored belts, and often paired with the kabalaki; a soft, turban-like headwrap.

Then there’s the papakha, a traditional wool or sheepskin hat: sculptural, somber, and deeply symbolic. Long associated with the highland men of Georgia, it has become a visual shorthand for pride and resilience.

Women’s Attire and Regional Artistry

Women’s traditional clothing, often referred to as kartuli, shifts dramatically from region to region, yet always retains a sense of elegance and intention. The centerpiece is a long gown, typically made of velvet, silk, or cotton, featuring a wide skirt and a fitted, embroidered bodice. The color palette—wine red, forest green, golden ochre—is never random; every shade conveys emotion, status, and occasion.

In the eastern lowlands of Kartli and Kakheti, women wore refined dresses with subdued hues, paired with velvet headpieces and fine veils. Embroidery—often in gold thread or adorned with tiny pearls—reflected a blend of Persian and Byzantine motifs, filtered through a uniquely Georgian lens.

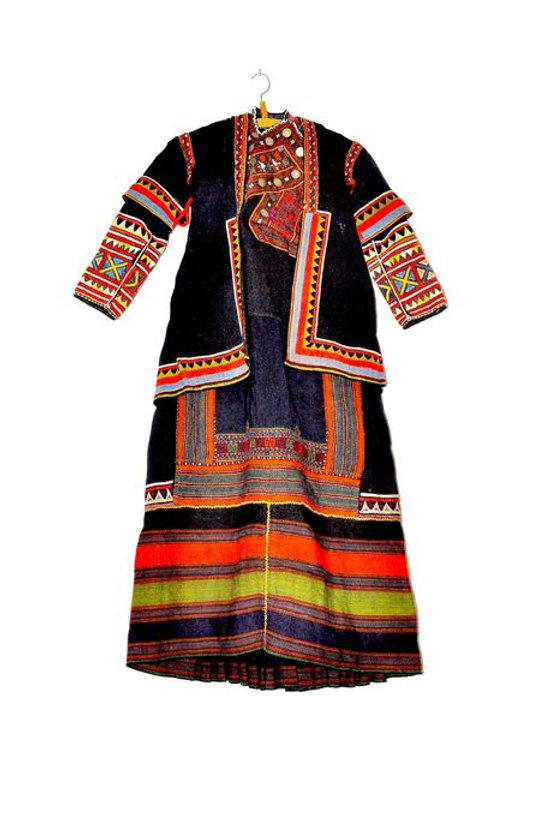

In mountainous Pshav-Khevsureti, dresses adapted to both harsh climates and spiritual beliefs. The sadiatso, a heavy short dress, was decorated with hand-sewn crosses and metallic charms meant to ward off evil. High, narrow headpieces were adorned with silver discs and sacred stitching—part protection, part ornament.

Further north in Tusheti and Svaneti, fashion turned more austere. Locally spun wool, wide skirts, and knitted footwear marked these rugged communities. Embellishments were practical but powerful: thick seams, earthy tones, and sacred symbols served both aesthetic and protective purposes.

Even in the more remote areas like Racha and Mtskheta-Mtianeti, garments carried a quiet opulence. Fabrics were often imported from Persia or Turkey and transformed through meticulous handcrafting: filigree, beads, and golden embroidery spoke of time, patience, and reverence.

The Language of Color and Embroidery

Every thread on a Georgian costume speaks a cultural truth. Black symbolized strength and nobility in the east; white and ivory, spiritual purity and youth; red, a tribute to wine, blood, love, and life. Gold and silver represented not only wealth but divine protection and light.

Embroidery was not mere decoration—it was storytelling. Spirals, flowers, crosses, and the Borjgali (an ancient sun symbol representing eternal time) were stitched into belts, bodices, and veils. Animal motifs—birds, deer, fish—connected the wearer to the natural world and ancestral spirits. In some regions, women encoded personal messages in their embroidery: love tokens, secret wishes, charms for luck or fertility.

Wedding Wear: A Ritual of Fabric and Symbolism

Traditional Georgian weddings were the height of sartorial expression. Brides wore flowing gowns in white or ivory, made from fine fabrics and heavily embroidered by hand. A red sash tied at the waist symbolized fertility and the transition into adulthood. Their faces were veiled in sheer fabric, crowned with jewel-studded or metallic-threaded headpieces.

Grooms appeared in full ceremonial chokha—dark, stately, with polished boots and a ritual dagger (kinjal) at the waist. In some traditions, the bride gifted the chokha to her future husband—a symbolic act of trust and unity.

The wedding itself was a theatrical celebration. Toasts, polyphonic singing, and the restrained beauty of the Kartuli dance (performed without touch, using only glances, bows, and poised movement) created a sacred choreography where the garments played leading roles in a silent drama of respect, love, and social harmony.

A Living Heritage: Revival in the Modern Era

After decades of Soviet suppression, Georgia’s sartorial heritage has roared back to life. The chokha has returned to public life as a proud emblem of cultural identity. Contemporary brands like Samoseli Pirveli produce it with modern tailoring, while designers like Machabeli and Woyoyo draw on traditional patterns to create fashion that feels ancient and avant-garde at once.

Even ancient knitting and textile techniques, dating back to 3000 BCE, are being rediscovered. Labels such as 711 and LTFR are reviving indigenous wool and dyeing methods, proving that craftsmanship, like memory, can be both timeless and trendsetting.

In Georgia, tradition is not tucked away in museums or archived in books; it walks the streets, graces the stages of folk dances, and whispers from the folds of embroidered sleeves. The nation’s costumes are living artefacts: shaped by geography, faith, and craftsmanship, and now revitalized through the hands of modern designers who understand that heritage is not meant to be preserved in glass, but worn, adapted, and celebrated. Much like the mountains that define its landscape, Georgia’s sartorial culture stands timeless—rooted deeply, reaching far.

Anna Olivo

Bibliography

N/A, “Costume Nazionale Georgiano” in Advantour https://www.advantour.com/it/georgia/tradizioni/costume-nazionale-georgiano.htm.

M. Aktaia Fava, “Sakartvelo e le sue vesti: lo splendore millenario degli abiti georgiani | Sakartvelo and its garments: the millenary splendour of Georgian costumes”, in Globus Rivista, https://www.globusrivista.it/sakartvelo-e-le-sue-vesti-splendore-millenario-degli-abiti-georgiani/, 18/03/2025.

“Borjgali” in Wikipedia, https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Borjgali.

“Čocha” in Wikipedia https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C4%8Cocha.

N/A “Costume nazionale georgiano” in Dresses Techninfus, https://dresses-it.techinfus.com/kostyumy-nacionalnye/gruzinskij/.

N/A in Guide et Voyage Géorgie https://guide-voyage-georgie.com/it/cultura-e-religione-in-georgia/abiti-tradizionali-della-georgia/.

N/A in Georgia.To, https://georgia.to/it/national-costumes-of-georgia/.

“Khevsureti” in Wikipedia https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khevsureti.

S. Parkosa, “Georgian National Clothes” in Georgian Market https://www.georgianmarket.com/blogs/news/georgian-national-clothes, 5/04/2024.

L. Satenstein, “You’ll Never Guess Which Country Is Having a Throwback Style Moment” in Vogue, https://www.vogue.com/article/tbilisi-georgian-traditional-fashion, 18/11/2015.

L. Satenstein “What Is Georgia’s Traditional Chokha and Why Is It in Fashion?” in Vogue, https://www.vogue.com/article/georgia-traditional-chokha-fashion-trend, 5/05/2017.

N/A, “Tradizioni nuziali georgiane” in Shahina Travel, https://eurasia.travel/it/georgia/traditions/wedding/.

“Papacha” in Wikipedia https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Papacha.